|

FROM LAKE COMO TO LONDON AND BEYOND

An explanation of how, when and why the young men of Lake Como found it economically and personally expeditious to remove

themselves to London and other cities of Europe to ply their trade, together with some contemporary observations on these

individuals that are not in Banfield's book (see book list)

The common Italian trampers have, from the first, had an entire monopoly of the weather glass department….

The Mechanics' Magazine, Museum, Register ..., Volume 15, Issues 395-424

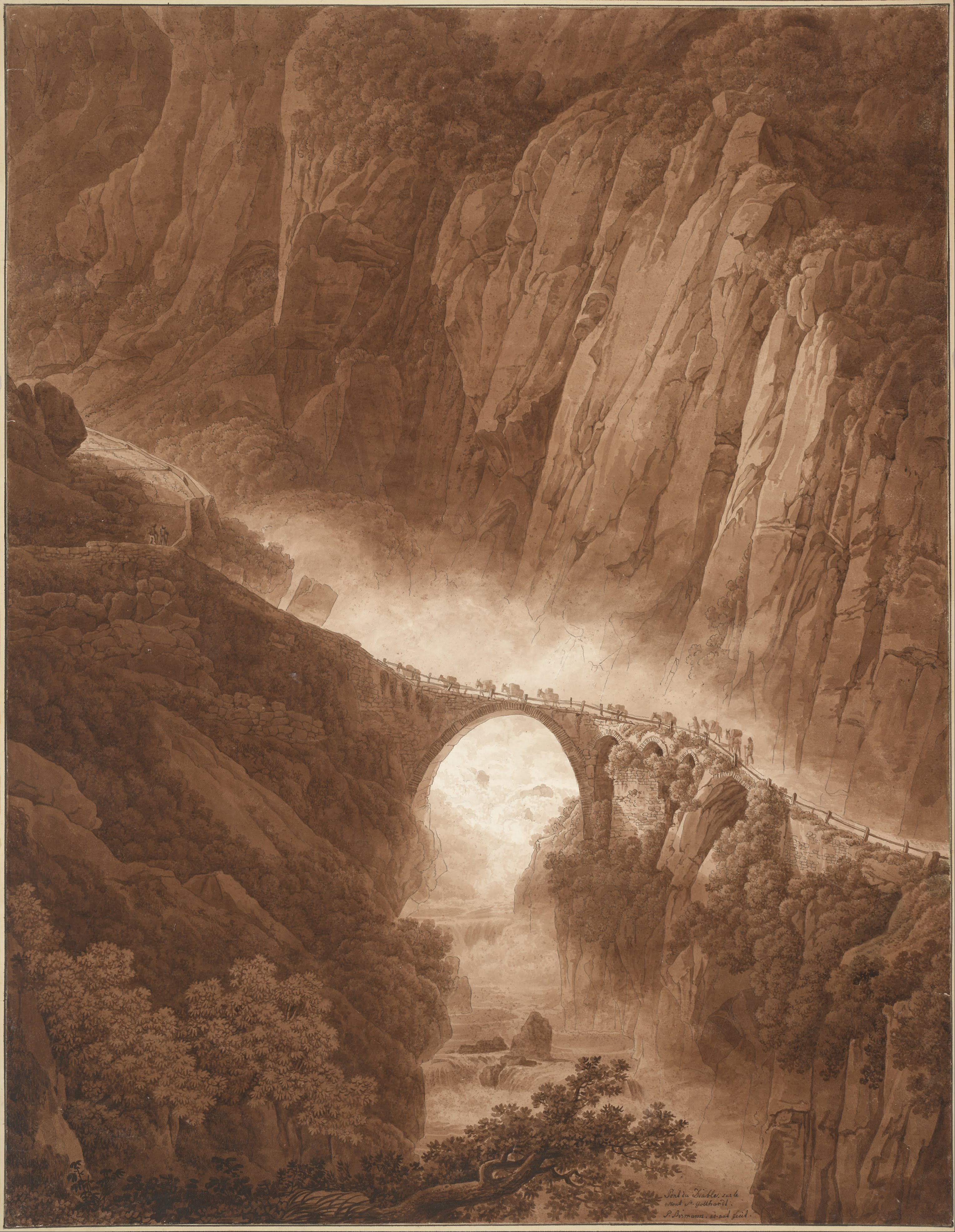

| Lake Como in 1830 by William Miller |

|

|

| from The Landscape Annual for 1830. The Tourist in Switzerland and Italy. Roscoe, Thomas. |

During the last quarter of the 18th

Century a small number of Italians, mostly young and, as far as is known, exclusively male, left their towns and villages

around Lake Como and came to Britain. In London and the largest cities they established the foundations of the Anglo-Italian

communities that, a century and more later, gave us not only ice cream for the masses but that national take-away: fish’n

chips. These early migrants, however, were skilled carvers, gilders, glassblowers and scientific instrument makers, and they

were particularly known for their barometers. While the scientific observation of atmospheric pressure lay behind

their craft, the everyday experience of economic pressure encouraged their departure. They were not the first to come to England:

Italian dancing masters and musicians were also known, but this small ripple - you cannot call it a 'wave' let

alone a flood, became a settled community.

It can't be overstressed that Italy was a geographic not a political

entity. For centuries various parts of it were ruled by other nations - Spanish, French, Austrians, Arabs... And the

rest was fragmented into city states. It's arguable that Italy still is a fragmented country. At this period, Lombardy

was ruled by the Hapsburgs, the Austrians, who were more interested in what Lombardy could do for them than what they could

do for Lombardy. Right at the end of the century the economic situation further deteriorated as a result of the French

Revolutionary Wars, when the French not only invaded this Austrian-held province of northern Italy but began to conscript the

men of Lombardy into their army. The young men from Como knew from compatriots who had gone north,

especially to France, Germany and Holland, that there was likely to be a market for their skills. Few probably intended

to emigrate forever: they saw themselves as migrant workers doing their best for their families back home and with the

ultimate aim of returning to lead a more prosperous life thanks to their foreign earnings.

There are numerous references to the barometer

makers of Como in the contemporary writings of travellers to the region.

At the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 , Sir Thomas Charles Morgan and his second wife, the Irish-born novelist

Sydney Owenson, embarked on a long tour of France and Italy. She wrote a book about each, to which he

contributed the footnotes. Of Como she wrote:

Although

the Lake of Como has lately been, and still is, the chosen retreat of ‘Chiefs out of war, and statesmen out of place’,

and although human habitations crowd to disfigure its beautiful shores, it wears a character of desolateness, silence, gloom,

and sequestration, which is singularly impressive. The many black dismantled buildings which skirt its shore…add much

to the dreariness of the scene. And the absence of all land communication (there being no roads along the whole tract of the

lake except to the Villa d’Este) deprives the country of those rural sounds and rustic imagery without which no scenery

is lovely. The scream of the water-fowl, the toll of the church bell at all the canonical hours, the measured beat of the

oar, and in the evening the wild choruses of the inhabitants of the innumerable paese, that lie along the lake, are,

however, appropriate sounds, and well become the deep solitude and romantic character of the scene.

Occasionally, an Italian would take his British wife and children back to Italy,

where the cost of living was less, even though he himself continued to work in Britain.

What was the attitude to these migrants when they reached Britain? Banfield and Goodison both quote the 1819 Cyclopedia

in its complaint against the wheel barometer which had lately obtruded on the public by strolling Italian hawkers in our

streets, decrying the imperfect execution and the defective principle which made them mere mechanical

pictures, and not scientific instruments, in the parlour. It certainly suggests people were happy to

buy their barometers, and the Italians soon came to dominate the market. Travellers seem to have enjoyed their encounters

with these exotic often itinerant emigrants; fellow Italians were not necessarily so kind to them, using them as the

butt of jokes. One reason may have been their dialect, so hard to understand that in 1845 Pietro Monti published in Milan

a dictionary to help his fellow Italians: Vocabolario dei dialetti della città e diocesi di Como. [With]

Saggio di vocabolario della Gallia cisalpina e celtico e Appendice al Vocabolario. There is a hint, too, that they were

not always viewed with respect in Britain, as can be seen from this 1817 letter by William Stewart Rose, published as part

of Letters from the North of Italy: Addressed to Henry Hallam Esq, Volume 1, London, John Murray, 1819. He had reached

the Italian lake region of Maggiore and Como:

You know the class of Italians who wander about the world with prints and barometers. These are considered in England

as Jews, but are, in fact, generally speaking, natives of the banks of the lakes of Lombardy... One ruling passion, the love of gain, distinguishes them all. One of these men had embarked with us at Paris,

as an outside passenger, and appeared to me little short of an idiot... But to give them honour due, though miserly, they are not dishonest, and are singularly sober, active and industrious.

TO ENGLAND

In the modern age of fast trains and air travel to Milan, the journey from

Como to England takes less than a day. Using motorways and tunnels, the 750 miles can safely be completed

by car with just one overnight stop. The emigrating Italians must have walked much of it while carrying their heavy packs

of barometers, thermometers, mirrors, and other wares made during the winter months.

The ‘favoured’ route before 1799 was to go north from Como, across Lake Lugano,up

to Airolo and over the St. Gothard Pass. It is not designed for vertigo sufferers. On the northern side, at Andermatt,

the wild waters of the River Reuss crash down the Schöllenen Gorge. The travelling Italians would have crossed this via

the narrow 16th century stone ‘Devil’s Bridge’, a structure which had been improved in the 1770s

to take carriages but not stagecoaches. J.M.W. Turner painted a number of dramatic views of this route, inspired by

his travels in Switzerland in 1802, which can be seen at:-

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/turner-the-devils-bridge-st-gothard-tw1813

they are certainly worth a look, but for copyright reasons cannot be shown on the website. Foot travellers, many with

packs, are clearly visible. In fact, when Turner saw it, the bridge must have been recently repaired following severe damage

by the French army in 1799.

| Crossing the Devil's Bridge |

|

| peterBirmannTheDevilsBridgeGoogleArtProject.jpg |

| The Devil's Bridge |

|

| The moden road bridge is built over the old one |

The

bridge still exists, below the one that superceded it, as you can see in the image above. and there's a good viewing

place if you happen to be passing. From Andermatt the road took the emigrants past the Swiss lakes and into France

at Basel. Travelling up the Rhein or taking the land route through France, perhaps staying with expatriates in cities such

as Paris or Rotterdam, the migrants reached the coast and could embark on a ship for England. Some emigrants did not

come directly from Italy to Britain: they had family businesses established in other European cites and 'expanded'

into Britain.

For the very earliest

it must have been daunting to arrive in the noisy, crowded capital of this flat, unfamiliar country. They did not speak the

language, there was no established Italian community to show them the ropes, no state assistance, no official leaflets

in Italian to help them or inform them of what few rights the ordinary working man enjoyed.

Most British barometer and scientific instrument makers were

established in London, and it was to London the Italians gravitated. The London Land Tax Records show the first Italian

makers scattered across a few streets to the north of Holborn, in the parish of St Andrew Holborn: Leather Lane, Greville

Street, Charles Street, Kirby Street, Cross Street, Hatton Garden and the small courts and passages that led off and behind

them. They settled there because it was a prosperous area of skilled craftsmen. Holden’s Triennial Directory, 2nd

Edition, 1799, includes addresses in the Holborn area for craftsmen such as: Adams, Umbrella maker; Michael Atkins watch pendant

maker; J Bird, watchmaker; Samuel Archer, watch, clock and patent pearl manufacturer.

Manchester, however, became

home to the Zanettis, Casartellis, Bolongaros and Ronchettis, though one of the best-known of the last-named clan established

himself in Holborn. Here, the industrial revolution offered particular opportunities for the scientific instrument makers,

and the Casartellis became influential for decades, in Liverpool, too, even supplying the meteorological information that

appeared nightly in the Manchester Evening News. Liverpool's Casartelli building, recently erected on the site

of their old premises, bears testimony to their presence. Birth marriage and death records point to some Italians setting

up in business very early in the 19th century in provincial towns. For example, the Barellis were well established in Bath

by 1804.

Much has been written about the squalour in which the Italian immigrants lived in Holborn and Clerkenwell

when it became known as 'Little Italy', but that was some three decades away when the skilled migrants

were followed by significant numbers of unskilled organ grinders, beggars etc and their families.

It seems clear that

the vast majority of late 18th/early 19th century barometers were made, whether by Italians or British, in London, and high

quality workmanship is an even stronger argument for London manufacture .That said, there exists a most beautiful wheel

barometer signed Donegan, Ship, Turnstile, London, which from information discovered during restoration was actually made

by an Italian working in Lewes, Sussex.

Italian emigrants who had been making or selling

their versions of the wheel – also called banjo - barometer, in other parts of Europe, soon found

that English tastes towards the end of the 18th Century were very different. The British favoured elegant neo-classicism rather

than exuberant gilded rococo, with mahogany as the most popular veneer. So the newcomers made or retailed barometers that

matched the Georgian styles of furniture above and alongside which they would be hung.

How did the settled community of Italian barometer makers in London, and doubtless in centres such as Edinburgh and

Manchester, sell their instruments? Some may have sold directly from their premises, others to wholesalers. Some

went travelling themselves or employed hawkers and pedlars. These itinerants might, for example, be family members or

someone who had come from the same Italian village as themselves. The difference between a hawker and a pedlar, by the way,

is that the former uses a cart or barrow to transport and sell his wares, while the pedlar carries his goods in a pack or

box. on his back. Accounts of pedlars carrying several barometers round their neck sound colourful, but have you ever tried

carrying one barometer around, let alone four or more at a time? A representative might rent a room in

an inn and sell their stock, then move on. They might also cold-call at farms. These pedlars should not be seen as one

step up from vagrants; they were not:

In

his The Italian Influence on English Barometers, Edwin Banfield quotes from novelist George Borrow's non-fiction

travelogue of 1862, Wild Wales, in which he described his meeting with an itinterant, but unfortunately unnamed, Italian

vendor of barometers etc. I am trying to use the clues to find out his name, but no success so far.

At length the landlady said, “There is an Italian in the kitchen who can

speak Welsh too. It’s odd the only two people not Welshmen I have ever known who could speak Welsh, for such you

and he are, should be in my house at the same time.”

“Dear

me,” said I; “I should like to see him.”

“That

you can easily do,” said the girl; “I daresay he will be glad enough to come in if you invite him.”

"Pray take my compliments to him,” said I, “and tell him that I shall be glad of his company.”

The girl went out and presently returned with the Italian.

He was a short, thick, strongly-built fellow of about thirty-seven, with a swarthy face, raven-black hair, high forehead,

and dark deep eyes, full of intelligence and great determination. He was dressed in a velveteen coat, with broad lappets,

red waistcoat, velveteen breeches, buttoning a little way below the knee; white stockings apparently of lamb’s-wool

and high-lows.

“Buona sera?” said I.

“Buona sera, signore!” said the Italian.

“Will

you have a glass of brandy and water?” said I in English.

“I never refuse a good offer,” said the Italian. He sat down, and I ordered a

glass of brandy and water for him and another for myself.

“Pray speak a little Italian to him,” said the good landlady

to me. “I have heard a great deal about the beauty of that language, and should like to hear it spoken.”

“From

the Lago di Como?” said I, trying to speak Italian.

“Si, signore! but how came you to think that I was from the

Lake of Como?”

“Because,” said I, “when I was a ragazzo I knew many from the Lake of Como, who dressed much

like yourself. They wandered about the country with boxes on their backs and weather-glasses in their hands, but had

their head-quarters at N. [Norwich] where I lived.”

“Do

you remember any of their names?” said the Italian.

“Giovanni Gestra and Luigi Pozzi,” I replied.

“I have seen Giovanni Gestra

myself,” said the Italian, “and I have heard of Luigi Pozzi. Giovanni Gestra returned to the Lago—but

no one knows what is become of Luigi Pozzi.”

“The last time I saw him,” said I, “was about eighteen years ago at Coruña in Spain;

he was then in a sad drooping condition, and said he bitterly repented ever quitting N.”

“E con ragione,”

said the Italian, “for there is no place like N. for doing business in the whole world. I myself have sold seventy

pounds’ worth of weather-glasses at N. in one day. One of our people is living there now, who has done bene, molto

bene.”

“That’s Rossi,” said I, “how is it that I did not mention him first? He is my excellent

friend, and a finer, cleverer fellow never lived, nor a more honourable man. You may well say he has done well, for

he is now the first jeweller in the place. The last time I was there I bought a diamond of him for my daughter Henrietta.

Let us drink his health!”

“Willingly!” said the Italian. “He is the prince of the Milanese of England—the

most successful of all, but I acknowledge the most deserving. Che viva.”

“I wish he would write his life,” said

I; “a singular life it would be—he has been something besides a travelling merchant, and a jeweller. He

was one of Buonaparte’s soldiers, and served in Spain, under Soult, along with John Gestra. He once told me that

Soult was an old rascal, and stole all the fine pictures from the convents, at Salamanca. I believe he spoke with some

degree of envy, for he is himself fond of pictures, and has dealt in them, and made hundreds by them. I question whether

if in Soult’s place he would not have done the same. Well, however that may be, che viva.”

The 1871 Census enumerated a Como-born hawker

of hardware by the name of Joseph (Giuseppe) Larico living in Denbigh, but he was 70 years old, so in 1854, when

Borrow made his Welsh tour, the man would have been in his 50s, not around 37. The men I have found who were born

around the right period, circa 1817, all seem to have settled jobs around the country and in London. Gestra,

Pozzi and Rossi are all recorded as having some involvement in the making or selling of barometers. Kristel de Wulf

italiansinnorfolk@gmail.com has posted online some excellent research into Giacinto Rossi https://sites.google.com/site/italianimmigrantsinnorfolk/home/database/rossi-giacinto

On the basis that websites have a habit of disappearing, I have taken the liberty of making a precis of the information,

but there's more on her site.

George Rossi was born on 20 Jun 1795 in Trezzone, Como, Lombardy and married

Elizabeth Molton on 4 Sept 1821 in London. She was a Norwich-born girl, daughter of another Italian barometer maker, Francesco

Moltino and his English wife Frances [Stannard]. Francesco Molton anglicised his name to Francis Molton.

The couple lived in Norwich and had 8 children before Elizabeth’s death in1833 . All were baptised into the Catholic

church. Two years later Rossi remarried, with Elizabeth Flood, and another eight children resulted from that union. Trade

directories list him as follows. - 1822 Pigot Norfolk, p. 305, looking glass maker, St Lawrence

- 1830 Pigot

National, p. 578, optician and looking glass maker, 14 Exchange street

- 1836 White Norfolk, p. 135, 205, 209, optician,

barometer & thermometer maker, silversmith & jeweller, 14 Exchange street

- 1839 Pigot National, p. 497, 499,

optician, silversmith & jeweller, Market place

- 1842 Blyth Norwich, p. 218, 221, 229, optician, barometer &

thermometer maker, picture dealer, silversmith & jeweller, Market place

- 1845 White Norfolk, p. 201, 202, 205,

optician, barometer maker, picture dealer, silversmith & jeweller, Market place

- 1846 Nine Counties Post Office

Directory, 1272, 1700, watchmaker & jeweller

- 1850 Hunt East Norfolk, p. 74, 76, 81, optician, picture dealer,

silversmith & jeweller, Market place, res. Mount pleasant

- 1850 Slater, p. 83, optician, Market place.

George

Rossi became a naturalised British citizen and he died on 22 November 1865. A blue plaque was put up at 9 Guildhall Hill,

Norwich to honour him. To that information I can add that he died in his home in the village of Eaton, near

Norwich, and left between £6,000 and £7,000.

Giovanni Gestra is recorded as a 'maker'

or seller of barometers and several of his instruments have come up for auction or sale; for example, in 2007 Bonhams

sold a neat Sheraton dating from around 1820 and signed Gestra, Newport. In fact the three barometers I have traced are all

signed gestra, Newport. On 1 August 1837 a certificate of his arrival at Dover was recorded. if this is the same Giovanni,

it is unlikely to have been his first arrival, to judge by the Borrow's memory and the evidence of the barometers he signed.

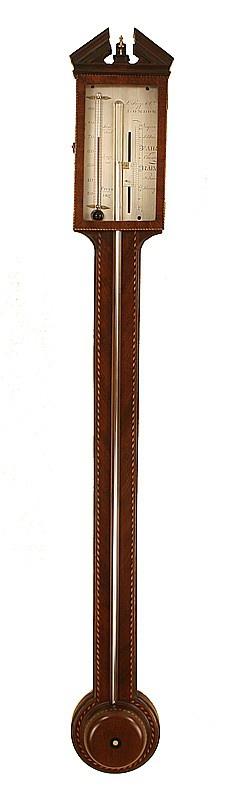

The very beautiful stick barometer with ivory and ebony rope inlay, illustrated below, is signed

L. Pozzi, London and was sold in October 2013 by P.A. Oxley. Unfortunately, not to me. Oh to win the Lottery.... It

dates to around 1810, which fits. If Pozzi was in his 60s in the second half of the 1830s that points to a date of birth of

1770-1780. |

| Luigi Pozzi Stick barometer |

|

| Courtesy of P A Oxley |

The Parish records of Stanton Lacy, Bitterley Shropshire: show that on 2 Jun 1812 Louis Pasquila

Pozzi, a travelling Italian having no settled place of residence, but 'late of this P'. married one Sarah

Weaver. This could be Borrow's Norwich and Corunna acquaintance as we know he was a pedlar. Sarah Pozzi

died at Ludlow towards the end of 1845, probably the same woman of 'independent means' who was enumerated

at Cowe/Cove Street Ludlow in 1841. That census didn't give status - as in married, single, widowed etc. She was aged

50, so very much in the right age group to have been the wife of Luigi Pozzi in 1812, but if she is, does this mean that

Pozzi left her behind when he went to Spain? One thing is very likely: that these Pozzis, even if not one and the

same, are very likely to have been related.

Some immigrants did well for themselves until, like Zanetti, they were able to start profitable

businesses in Britainand either remain or return with their wealth to Italy. The famous Macclesfield furniture shop,

Arighi Bianchi, which dates from, the mid-19th century and is still going strong (has the most superb cafe with

scrumptious, artery-clogging gateaux) was, according to the company history, founded on the sale of barometers to local

farmers on a cunning try-before-you-buy system. A close-fisted farmer who became dependent on a barometer craftily 'left

in his care' for a few weeks was very likely to buy it when the pedlar returned to collect it.

The following pages are devoted to the lives and barometers

of one family: the Ortellis.

Enter content here

|